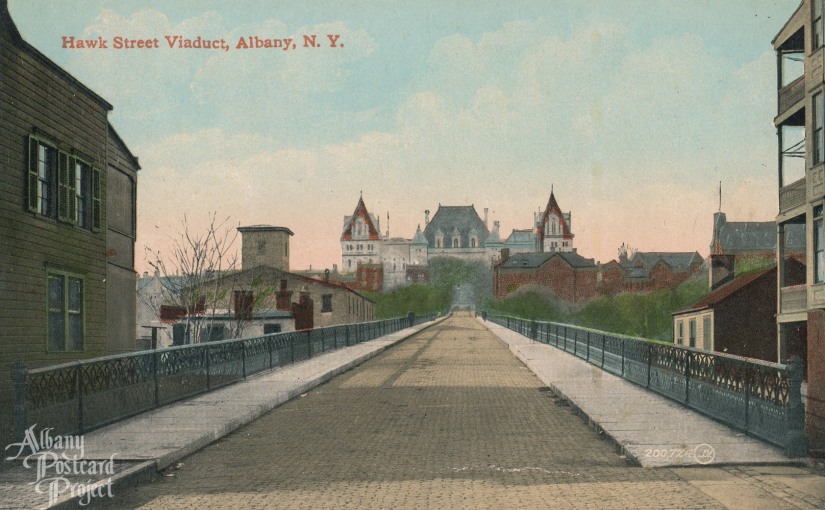

…was in Albany, New York. Kind of surprised me, too. While poking around on the fabulous Albany Postcard Project, I found this image:

That’s a bridge I’ve never seen.

Apparently, there was once a time, not so long ago, that Arbor Hill residents had their own bridge, one that led right to the doors of the Capitol. It had a beautiful web of steel girders that carried Hawk Street for nearly 1,000 feet from Clinton Avenue, over the rooves of Sheridan Hollow, to Elk Street.

It was known as the Hawk Street Viaduct.

Though the idea for the bridge originated much earlier, the contract for its construction was awarded in December 1888. It went to the Hilton Bridge Construction Co., then led by Elnathan Sweet, who had just come off a stint as the State Surveyor and Engineer, a now defunct cabinet-level position. He had impeccable engineering chops, especially when it came to railroad bridges, and his design for the viaduct showed it.

Instead of opting for the tried and true cantilever truss, Sweet designed a cantilever arch, centered on a three-hinged, two-rib, 360-ft main arch. Springing north and south from either end, and supported by nothing more than the main arch, were 114-ft half arches. These were the cantilevers. Twin 66-ft end spans sprang from abutments on the ravine rim to meet the cantilevers. The use of hinges in such a way was by no means novel at that time, but incorporating them meant that the structure could adjust to the varying temperatures and load. Construction started in 1889 and finished the next year, during which time workers used more than 800 tons of iron and open hearth steel to build the 986ft span. It was then paved in creosote-coated pine blocks, lined with pedestrian walks, stairs from the streets below (Orange and Spruce streets), and given a highly ornamental though perhaps not especially safe wrought iron railing.

Once it began, construction went rapidly. By mid-December 1889, both halves of the bridge were connected, and paving of the western portion had begun. Work was complete by early spring 1890 and it was almost ready to open to the public. But it first needed to be inspected by the City Engineer and Street Commissioner. In their report, they made several routine recommendations, such as that it be painted every few years to deter corrosion, and that the stairs at Spruce and Orange streets be removed (for unknown reasons). They also noted that:

Owing to the nature of the construction of the bridge, it is peculiarly liable to injurious vibrations from the passage of bodies of men keeping step, and from the trotting of men keeping step, the rapid motion of herds of cattle, etc.; these should be prevented by suitable fines and penalties.

Their concern about “men keeping step” might seem preposterous, but it was actually quite warranted. The phenomenon, known as mechanical resonance, had caused several bridges to collapse during the preceding decades. One such in Angers, France, killed more than 200. To my knowledge, resonance was never an issue on this bridge, despite being used for major parades in its early years. What I know was deadly was it’s height. The bridge was highest above the ravine where it crossed Sheridan Avenue, at about 79 feet (various heights are given over the years). That height, combined with the short iron railing, made it one of the places where souls who wished to take wing for the afterworld took flight.

Even though the bridge lacked the visual poetry of those over water — the nearby structures obscured its graceful curves — the cityzenry were nonetheless proud of their new viaduct and boasted about it in the papers. (Take that, Troy!) They had reason to be proud. Not only was it a monumental work visible from across the valley, it was also the first bridge to combine an arch with a cantilever. That novel design was so well received that, in the following decades, it was copied for bridges over the Viaur and Seine in France, the Elbe–Lübeck Canal at Mölln in Germany, and for use on railways in Alaska and Costa Rica. But while the design of the Viaduct is intriguing, the story about how it came about — and how long it took — is perhaps even more so.

Another take on the Hawk Street Viaduct from the Friends of Albany History, and one from the (now defunct) All Over Albany.